Alongside writing for this magazine, I have been known to make the odd bit of music. If you have checked out my Relooped performance in the previous post, you will know that my definition of music is… broad. In this article, I will go into detail about a recent digital modular system that I built with a visual coding language by the name of Max.

Part One: Technical Description

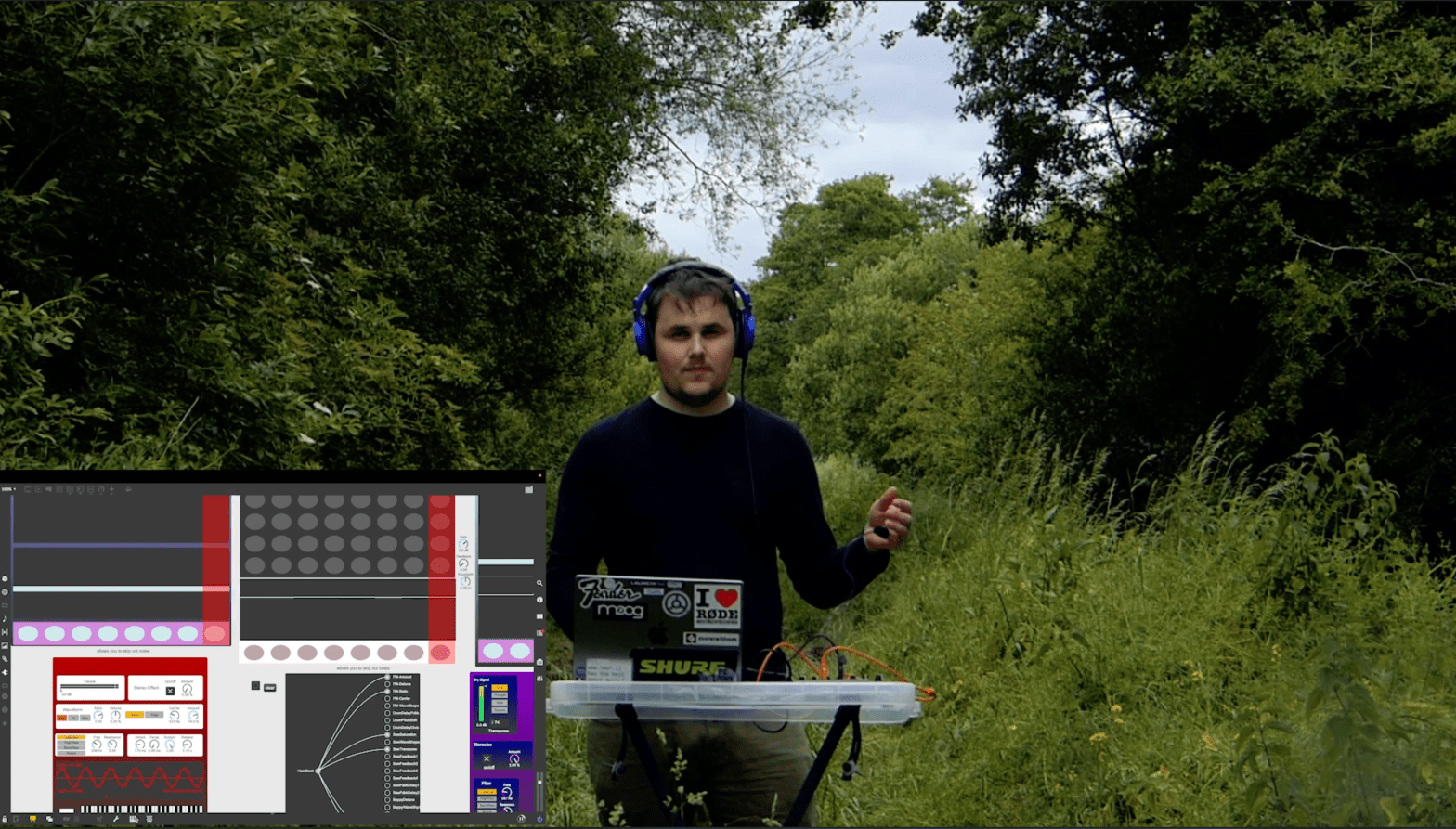

Basic project overview: A Max patch that comprises of sevaral different moduels. Each moduel has several parameters that are midi-mapped to a midi controller for live performance purposes. The unique part of this patch, however, is an Arduino with a pulse sensor attached. The Arduino feeds the beats per minute (BPM) data into the Max patch. The BPM data is then scaled and sent to various parameters at random. This affects the amount of control that the performer has over their performance and they must adapt to the changes as they go.

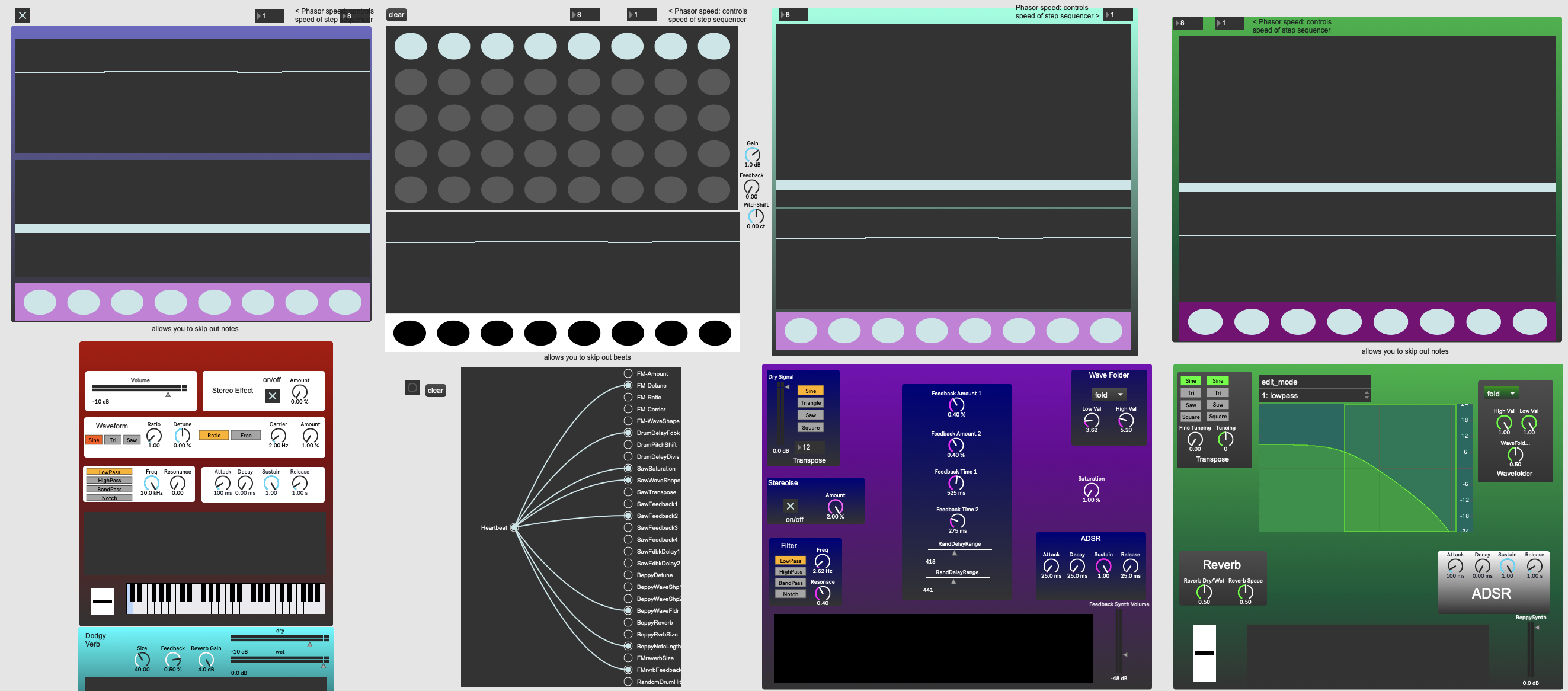

A challenge that I set myself in this project was to build each element from the ground up as opposed to using pre-built modules. This would allow me greater control and understanding of how my patch worked. The backbone of the patch is the step sequencer modules.

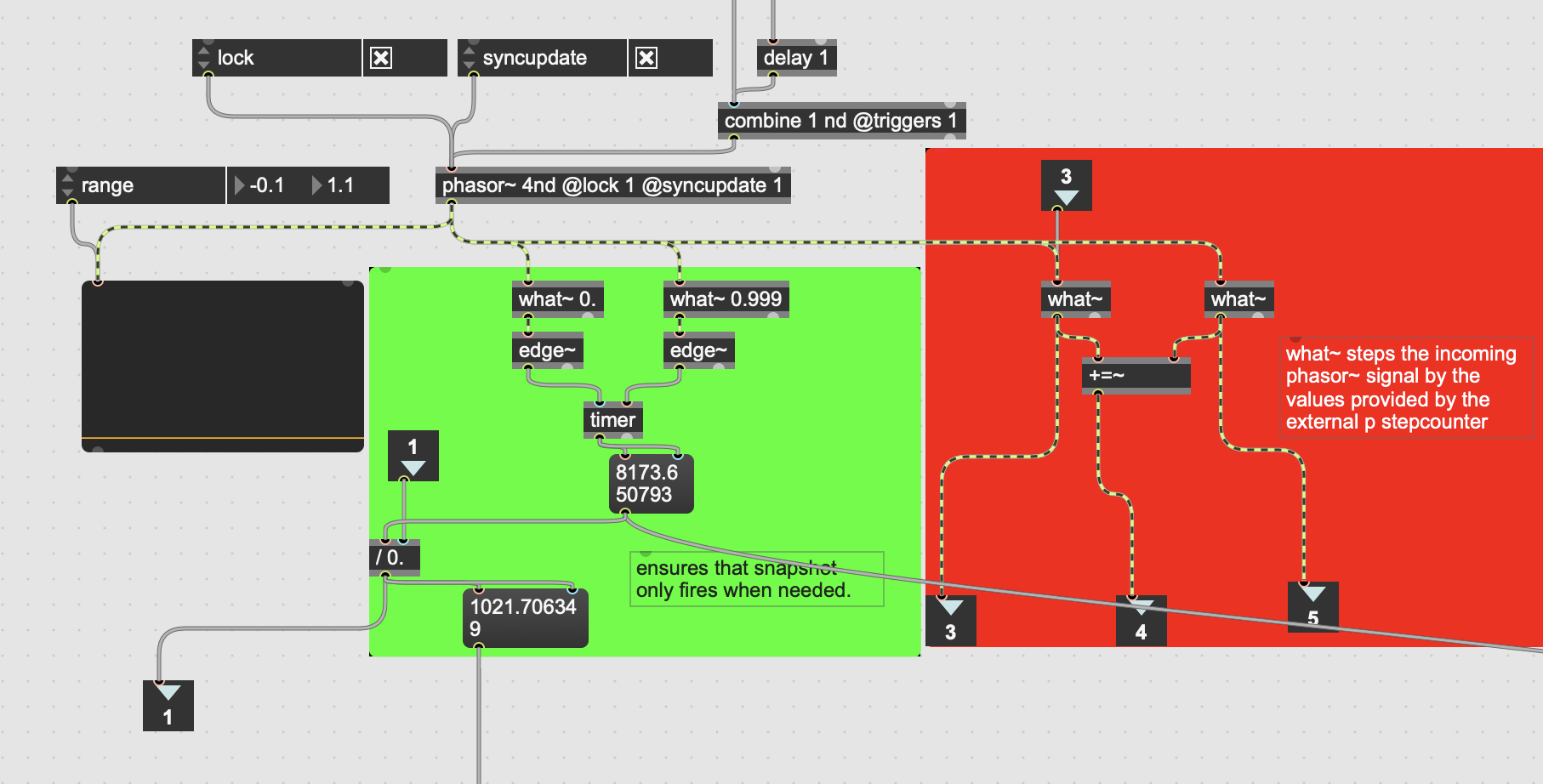

These modules use a Phasor~ object to keep time as they are sample-accurate. The What~ objects in the red box create block-like stepped signals when the phasor crosses a predefined threshold. A few extra calculations later and these signals have been scaled and converted into pitch data for the oscillators in the synth modules. The green box times the milliseconds between the start and end of each Phasor~ cycle. This timed value only became necessary when the BPM data was added later on and started to change parameters such as tempo. Without the exact time between step sequencer cycles, digital artefacts created by parameters changing mid-playback were destroying the overall audio quality.

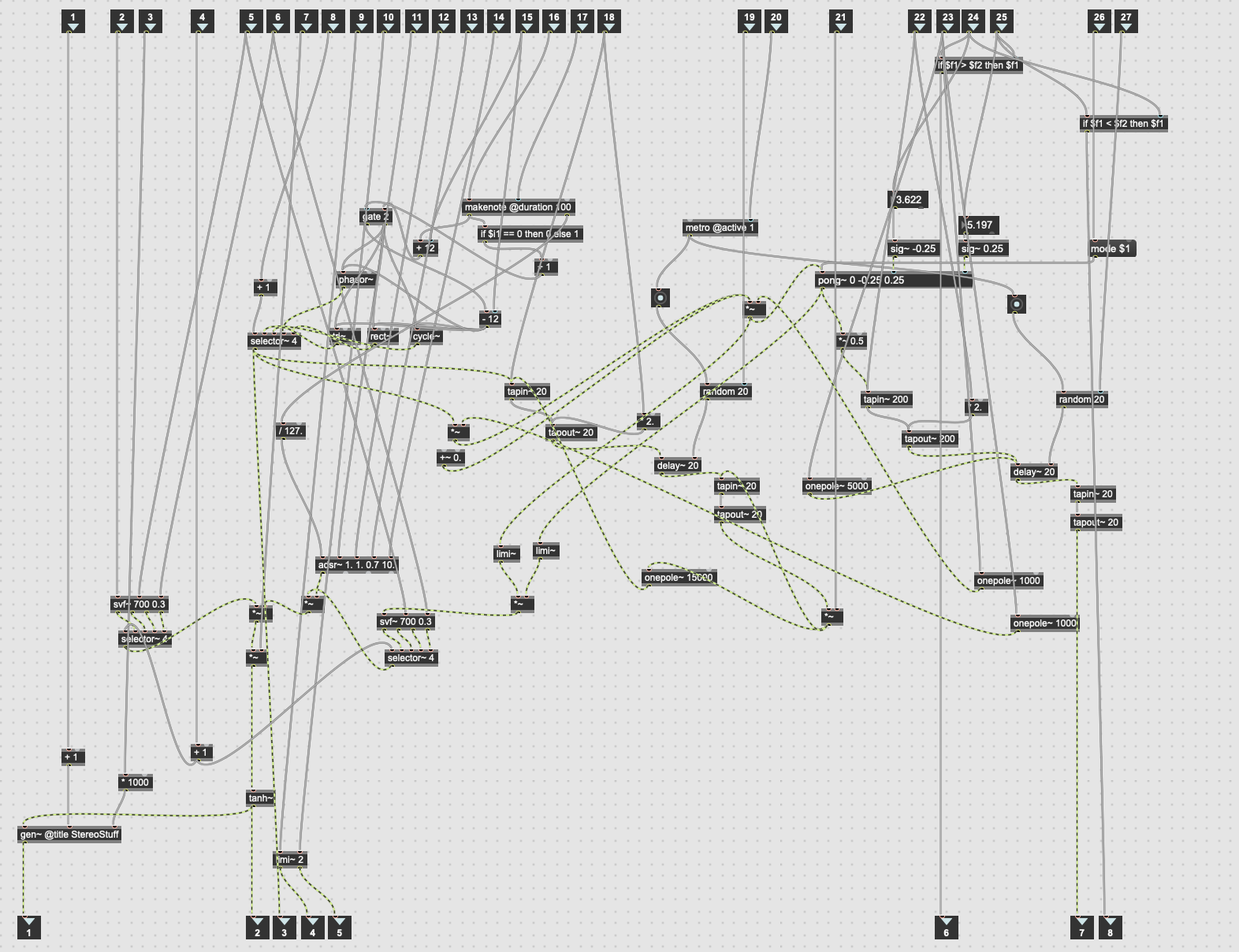

Another noteworthy module is the “SawSynth”. The idea behind this synth came from a question I had for Elevator Sound’s Ben Chilton during a eurorack workshop. I asked about the inner workings of a particularly rich oscillator. He replied that he did not absolutely know but thought that it was a collection of triangle waves being constantly fed back into themselves. I took this idea forward, making it my own by experimenting with delays, filtering and wave folding. The result of my experimentation is considerably unstable, however, its malleability makes it an incredible performance tool.

Another technical function that I want to highlight is an example of data processing. The BPM output from the Arduino proved to be an unpredictable source due to the read errors often made by the heart rate monitor component. The workaround for this required me to decide if having the heart rate display in real time was essential to the performance. This allowed me to switch from technical thinking to creative thinking. Realising that the heart rate was a performative aspect rather than strictly scientific, I used the Phasor~ step sequencer module to give me the exact milliseconds between every four beats. Because the Phasor~ object only updates its tempo when a cycle has been completed, this gave me a stable data source. I then divided the time in milliseconds by four and assigned the output to a Metro~ object. Although this is a less accurate representation of my actual heart rate, the performance benefited from the increased stability. The realisation that data accuracy does not always equal improvement was perhaps the biggest single learning experience in this project.

Part Two: The Context

This project felt like a combination of the largest points of interest from my university studies. The technical side of the project derives from a growing interest that I have in live modular synthesis performance. The most influential artist to me recently was Surgeons Girl, specifically her collaboration with Bristol Paraorchestra titled Trip the Light Fantastic. Seeing modular synthesis begin to push at the limits of its own genre boundaries made me curious to explore the inner workings. This led to the development of my self-generating techno Max patch, which in some ways almost acts as a prototype for this project.

The abstract side of the project was inspired by my studies on the life of John Cage and those around him. A large portion of Cage’s work was rooted in chance operations. Inspired by Zen Buddhism, Cage would compose Music of Changes using an ancient Chinese text, the I Ching. The text would decide the tempo, pitch and duration of each note. The intended outcome of such composition techniques was to remove any likes or dislikes that the composer may feel toward the music, thus freeing the music.

I am fascinated by these ideas and through this project, hope to continue the kind of experiments that Cage might have attempted if he had today’s technology. When deciding on this project, I did want to add an extra layer of depth to these Cagian ideas. I pondered the chance operation being triggered by the performer. Would they fight to control these seemingly random parameter changes? Would these chance operation compositions feel different to the listener if they knew it was generated by a human?

In an online environment overpopulated with AI-generated media, this patch attempts to ground the audience in one of the most recognisable sounds for a human, the thumping sound of life.